Third Hicatee Conservation Forum and Workshop

Developing a Conservation, Management, and Action Plan for the Central American River Turtle, Dermatemys mawii, in Belize

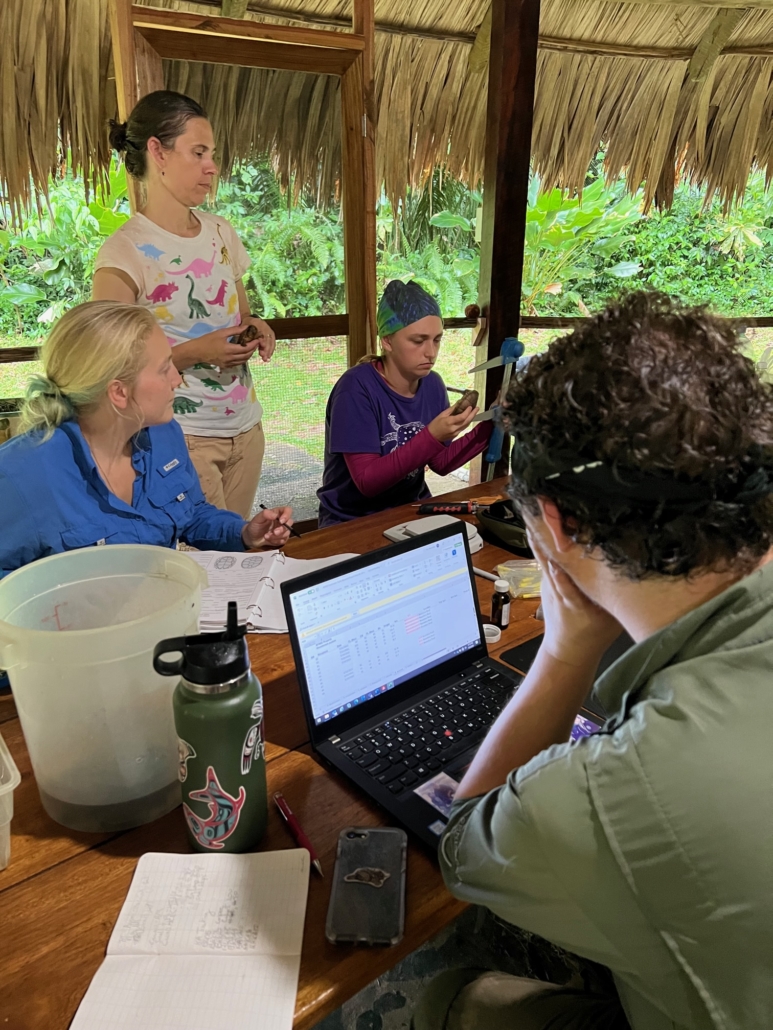

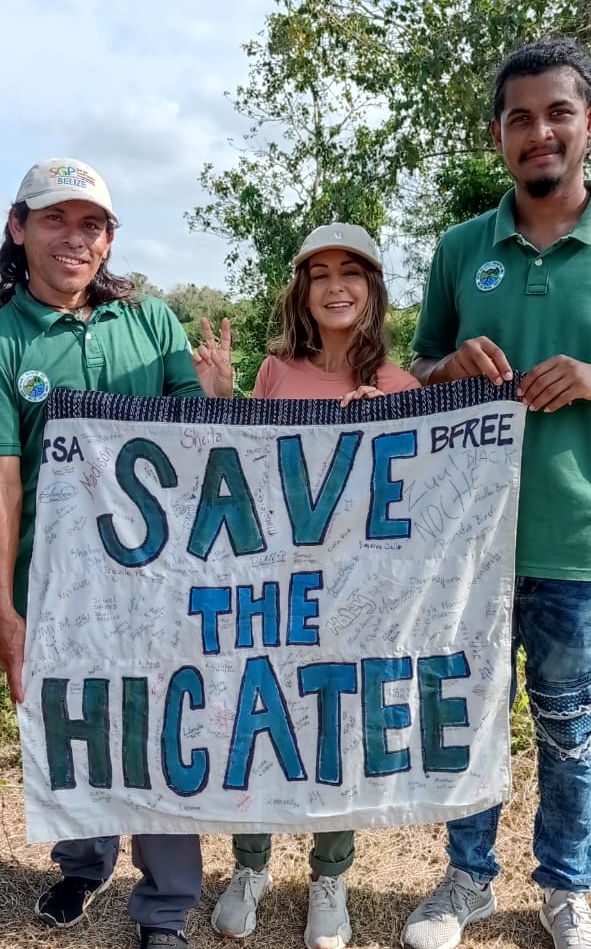

Co-hosted by Belize Foundation for Research and Environmental Education (BFREE), the Turtle Survival Alliance (TSA), Zoo New England (ZNE), and the Belize Fisheries Department, the Third Hicatee Conservation Forum and Workshop was held online via a Zoom webinar on May 17, 2022. The purpose of the Hicatee Conservation Workshop was to bring together stakeholders to begin to develop a Conservation, Management, and Action Plan for the Central American River Turtle in Belize. Organized by Dr. Ed Boles, BFREE Dermatemys Program Coordinator, with the support of BFREE staff, the workshop was facilitated by Ms. Yvette Alonzo with technical assistance from Mr. David Hedrick of TSA. The workshop was attended by 38 professionals supporting Dermatemys mawii research, conservation, and outreach, including key Government officials from the Belize Fisheries Department.

Hicatee Conservation Forum Breakout Groups

Participants divided into five breakout groups in previously identified focal areas of: Laws, Regulations and Enforcement; Community Outreach, Education and Social Research; Captive Management and Reintroductions; Biological and Ecological Research, and in situ Conservation. The groups were tasked with discussing background, ideas, and concerns for 59 proposed actions divided among seven conservation goals. Further they were responsible for modifying action descriptions, eliminating irrelevant actions, and adding actions the group identified as appropriate.

Hicatee Conservation Forum Participants

| Breakout Groups | Members of the Breakout groups |

| Laws, Regulations, and Enforcement | Felicia Cruz, Fisheries Officer, Belize Fisheries Department – Chair, Jacob Marlin, Executive Director, BFREE – (first half), Gilberto Young, Inland Fisheries Officer, Belize Fisheries Department, Peter Paul van Dijk, Red List Authority Coordinator of the IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, Thomas Pop, Hicatee Conservation & Research Center Manager – (first half), Debora Olivares (note taker) |

| Community Outreach, Education, and Social Research | Heather Barrett, Deputy Director, BFREE – Chair, Conway Young, Administrative Officer, Community Baboon Sanctuary, Jonathan Dubon, Wildlife Fellow, BFREE, Paul Evans, Outreach Officer, University of Florida, Emilie Wilder, Field Conservation Officer, Zoo New England |

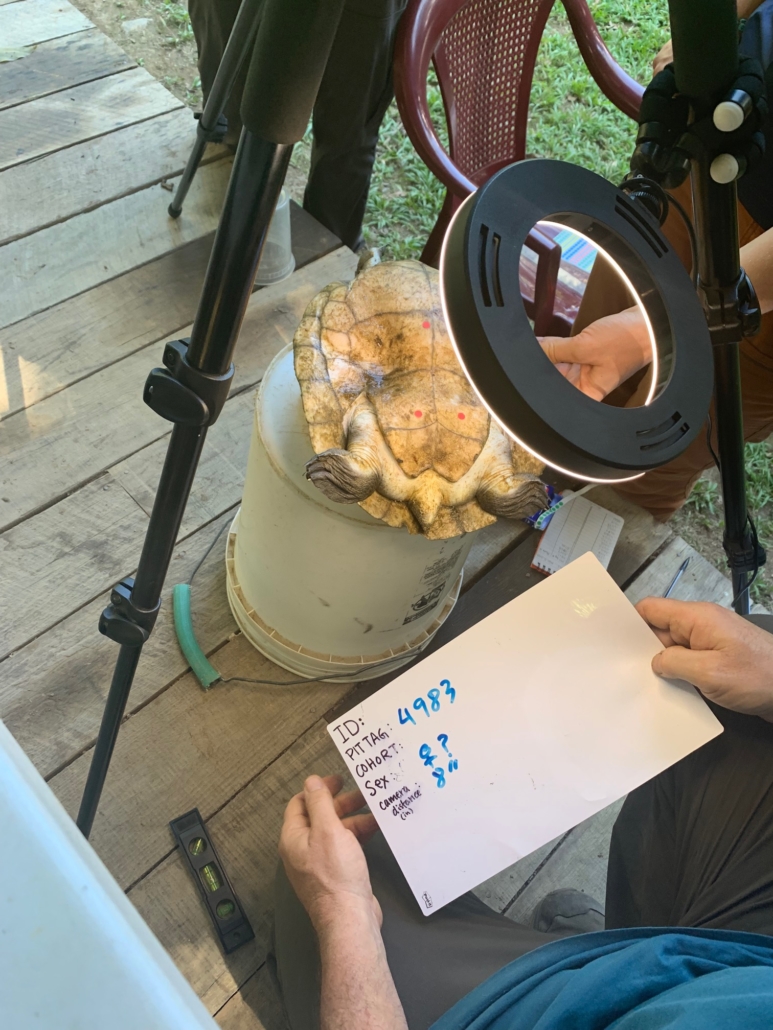

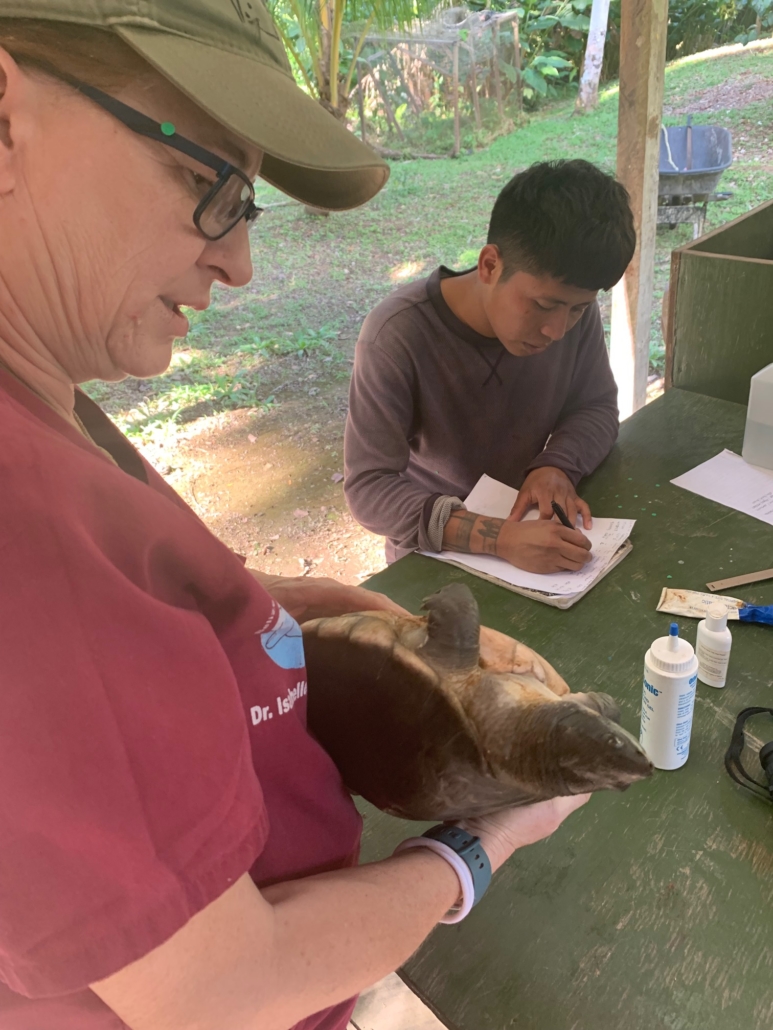

| Captive Management and Reintroductions | Bryan Windmiller, Director of Field Conservation, Zoo New England– Chair, Elliott Jacobson, Veterinarian, University of Florida, Brian Horne, Wildlife Conservation Society, Calvin Gonzalez, Outreach Officer, Belize Wildlife and Referral Clinic, Isabelle Paquet Durand, Veterinarian, Belize Wildlife and Referral Clinic, Dudley Hendy, Fisher, Jacob Marlin (second half), Thomas Pop (second half), Julie Lester (note taker) |

| Biological and Ecological Research | Day Ligon, Professor of Biology, Missouri State University – Chair, Boris Arevalo, Wildlife Conservation Society, Donald McKnight, Turtle Biologist, La Trobe University, Thomas Rainwater, Research Scientist, Clemson University, Venetia Briggs-Gonzalez, Director, Lamanai Field Research Center, Manual Gallardo, Olmaca University, Guichard Romero, D. mawii researcher in Mexico, Vanessa Kilburn, Director, TREES Eduardo Reyes Grajales, D. mawii researcher in Mexico, Jessica Schmidt (note-taker) |

| In situ Conservation | Andrew Walde, COO, Turtle Survival Alliance – Chair, Elma Kay, Managing Director, Belize Maya Forest Trust, Tim Gregory, TSA and BFREE Board Member, Yamira Novelo, Technical Assistant, Wildlife Conservation Society, Denise Thompson, Per Course Faculty, Missouri State University, Ed Boles, Dermatemys Program Coordinator, BFREE |

Workshop Results

Results of the workshop yielded a 33-page transcript capturing input from participants, which will serve as a supporting document for the compilation of the first draft of the “Conservation, Management, and Action Plan for the Central American River Turtle, Dermatemys mawii, in Belize”. A follow-up workshop to review the draft will take place later in 2022. Completion of an integrated and inclusive plan for Belize, guided by research and decades of traditional fisher experience, is the goal. If successful in this country, the content will be exported as guidance for similar plans in Mexico and Guatemala.

The overall theme of this very successful workshop can be described as taking actions to increase research, conservation, and restoration initiatives that are inclusive of local communities and the promotion of community-based management through the full D. mawii range. Farmers, fishers, youths, and all concerned citizens are recognized as vital partners in ensuring the survival of D. mawii into the future – a theme that shall be tightly woven into the resulting conservation, management and action plan.