Blog

My BFREE Experience

by Ashira Rancharan My time at BFREE was nothing short of magical. I’ve always loved nature, but being there felt different; I wasn’t just an observer and instead was a part of all that was happening. I’m someone who has always been a little hesitant about volunteering and afraid that I might not do things…

Read MoreHappy 30th Anniversary to BFREE!

Yesterday, I was filmed for a series of short videos we will be sharing in celebration of the thirty-year anniversary of BFREE. In the middle of the interview, the videographer said, “I think we need to find a quieter place, it’s too noisy here.” I agreed. The sounds of Scarlet macaws, Howler monkeys, and the…

Read MoreCreative Courses in the Jungle

The BFREE field station serves as an oasis optimal for artistic pursuit, retreat, and growth. January 2023 I spent two weeks at BFREE as an undergraduate student while completing a course called Travel Writing through Bethel University. When I registered for the course I knew almost nothing about the country of Belize and certainly did…

Read MoreAndrew Choco Joins BFREE Full-time as Wildlife Fellow

Hey there! My name is Andrew Choco, and I am from Trio, a community adjacent to BFREE. I was raised in Bella Vista Village, where my connection with nature was somewhat limited. However, after watching documentaries on Animal Planet, my interest in the natural world was sparked. These programs ignited a deep passion for wildlife…

Read MoreA professional crash course for cacao and chocolate lovers!

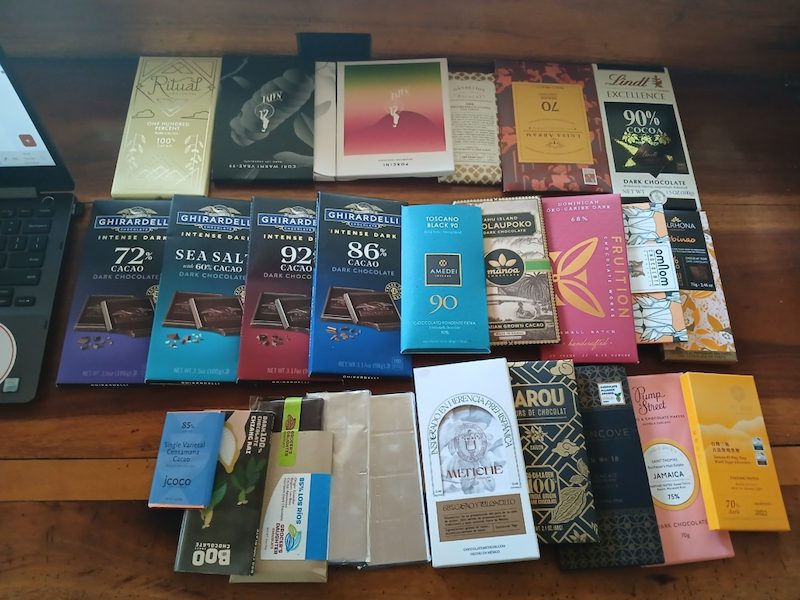

Recently, I participated in an exciting online training opportunity. The “Chocolate Making from the Bean Program” is a professional two-month course that began on September 27 and concluded on November 29, 2024. Participants who took the course, including me, came from various backgrounds and professions but all had a passion for chocolate! With seven years…

Read MoreA moment with Rachael Harff, Chelonian Keeper at the Turtle Survival Center

Q&A with Samih Young, BFREE Wildlife Education Fellow This summer, Samih Young and Rachael Harff got to know each other while participating in the Fourth Annual Turtle Survey of the BFREE Privately Protected Area. The survey is a collaboration between BFREE and Turtle Survival Alliance‘s Volunteer Research Team – also known as the North American…

Read MoreThe Bladen Review 2024

The 9th edition of BFREE’s annual magazine is now available in an interactive format online at Issuu! Get the latest news from the field station and learn about exciting research, conservation and education projects taking place in and around the rainforests of Belize. Highlights of the 2024 magazine include: updates on the conservation and outreach programs associated with…

Read More2025 Long-term Turtle Survey in the Jungle

July 6 – 16, 2025 Join the Belize Foundation for Research & Environmental Education (BFREE) and the Turtle Survival Alliance’s Volunteer Science Program to participate in a long-term population monitoring project for freshwater and terrestrial turtle species located within BFREE’s Privately Protected Area in southern Belize. The BFREE Privately Protected Area is a 1,153-acre reserve…

Read MoreCelebrating the 8th Annual Hicatee Awareness Month

Hicatee Awareness Month began in 2017 to draw attention to the status of Belize’s only critically endangered reptile, the Central American River Turtle locally called “Hicatee”. Eight years later, BFREE and our NGO international and local partners including Turtle Survival Alliance, Zoo New England, Belize Wildlife Referral Clinic, WCS Belize, Community Baboon Sanctuary and Savannah…

Read MoreReptiles through the eyes of a newbie: Wanna Be Herpetologist

Reptiles at BFREE At BFREE, a diverse range of reptiles thrive within its boundaries. I’ve been fortunate to encounter several species firsthand, from the slow-moving yet captivating turtles to the agile and vibrant lizards. My recent encounters with snakes have deepened my interest in these often misunderstood creatures, revealing the unique roles they play in…

Read More