Scaling-Up Local Stewardship: A Summer of Listening, Learning, and Advancing Freshwater Conservation in Belize

By Jaren Serano, Dermatemys (Hicatee) Social Scientist

During my work as Dermatemys (Hicatee) Program Coordinator, I focused on ensuring the Conservation and Management Plan for the Hicatee turtle was finalized and approved by stakeholders including the Belize Government. Through this process, I became particularly interested in the human dimensions of the conservation program for the species. Ultimately, this led to my pursuit of my PhD and a shift in my role at BFREE to Dermatemys (Hicatee) Social Scientist.

I entered a doctoral program in Wildlife Ecology and Conservation at the University of Florida and this summer; I began preliminary research. The work is a collaborative effort, grounded in the vision of scaling up local stewardship to support community-based approaches to freshwater resource management in Belize.

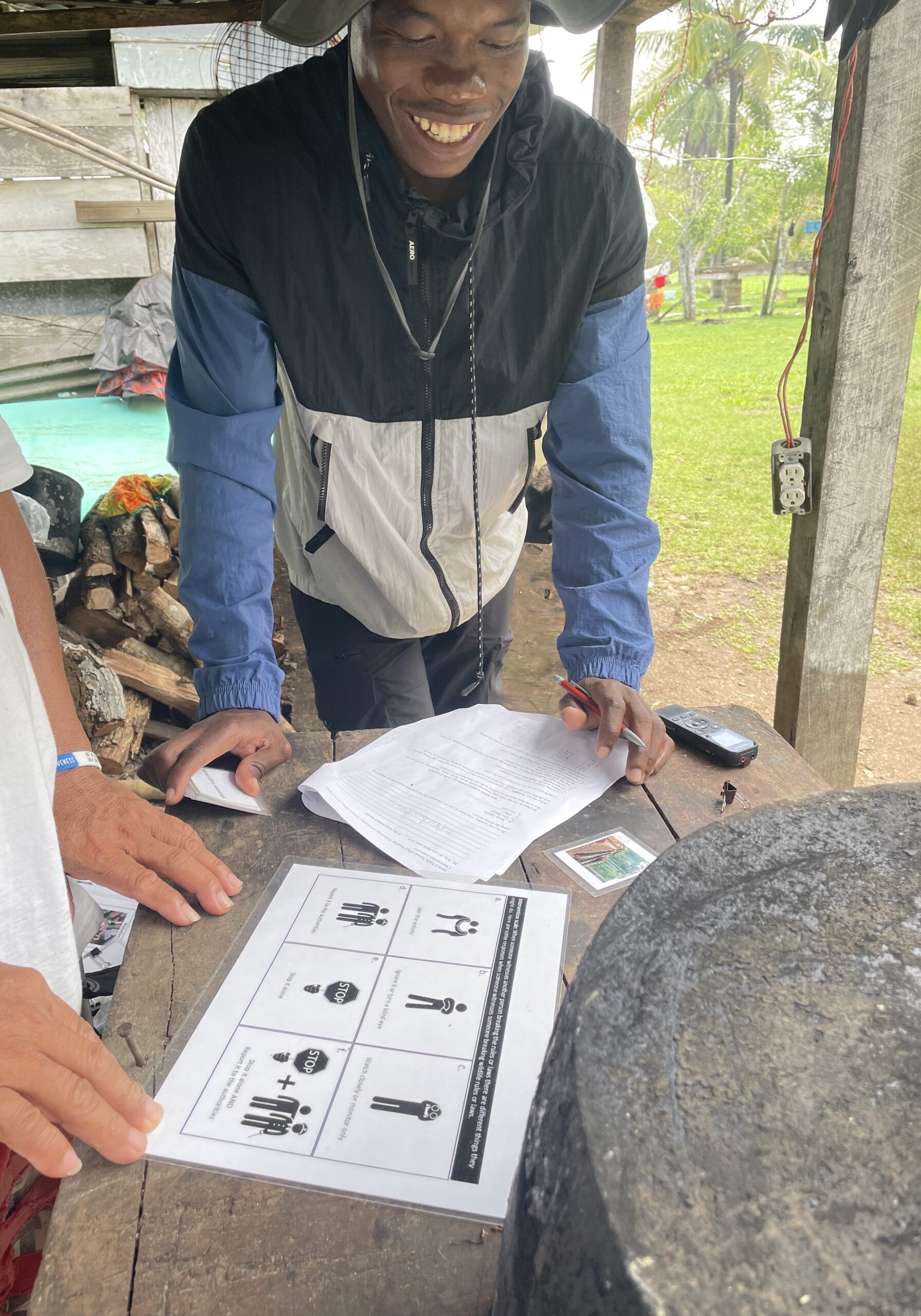

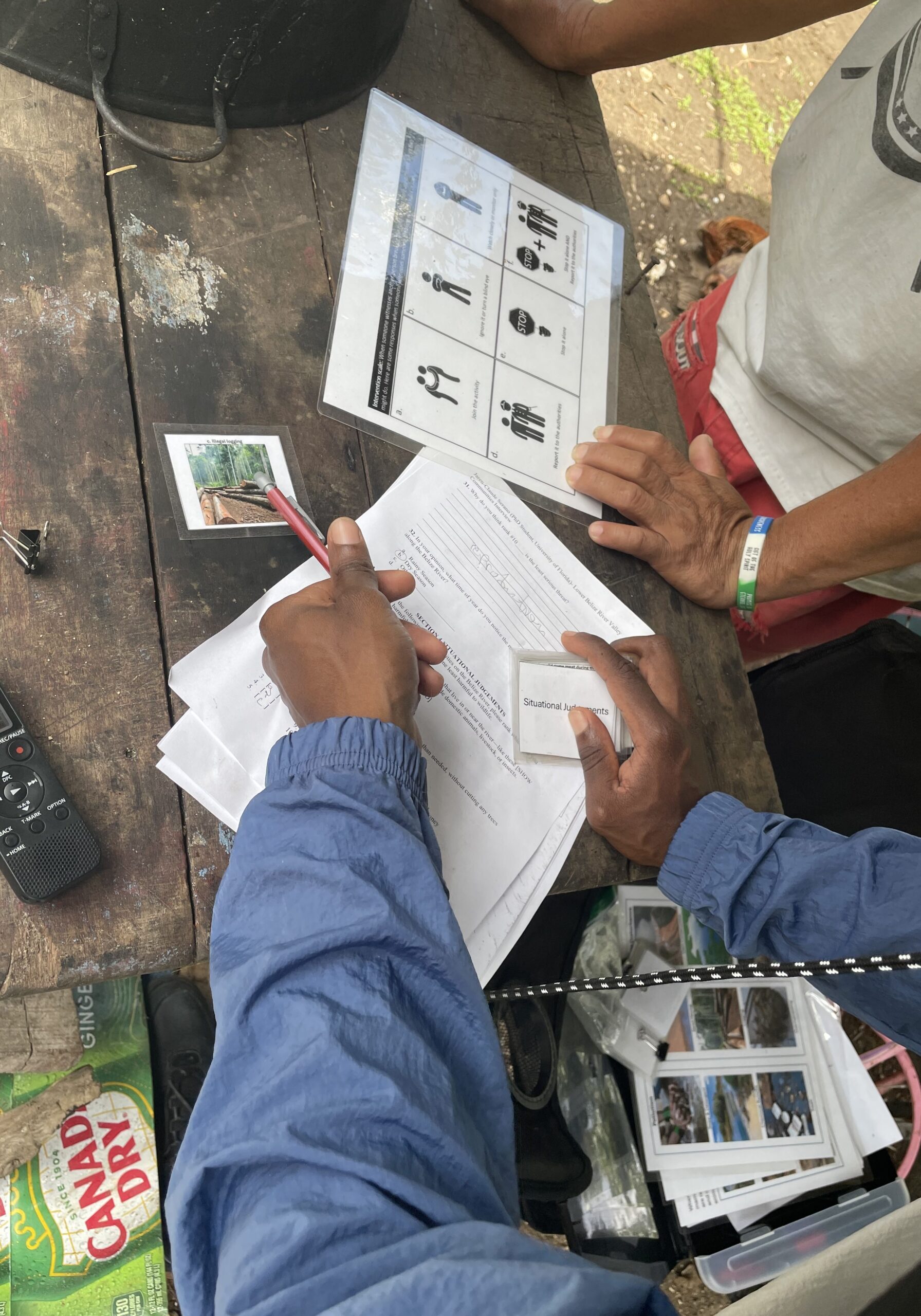

During these semi-structured interviews, I listened to community members to better understand how environmental change threatens local freshwater ecosystems. Photo by Samih Young

The Background:

In Belize, a large portion of the national population resides within the Belize River catchment, highlighting its importance as a vital socio-ecological system. The Belize River, the longest in the country, stretches roughly 180 miles from the western border through central Belize to the Caribbean Sea. It has long served as both a cultural artery and a lifeline, shaping the identities and livelihoods of the people who live along its banks.

During the Classic Maya period, the Belize River Valley was a densely populated and politically dynamic landscape. In the 19th century, the economic dominance of mahogany logging deepened the river’s material and social significance. The extractive industry became central to the Belizean economy and was tightly linked to the formation of Belizean Creole identity. As the mahogany industry declined, rural Creoles adapted by developing alternative systems of natural resource use, including small-scale agriculture, subsistence hunting and fishing, and seasonal labor, ways of life rooted in a reciprocal relationship with the land and river.

Today, Belizean Creole communities remain concentrated along the lower stretches of the Belize River, particularly in the southern and eastern regions known as the Lower Belize River Valley (LBRV).

Hicatee turtle (scientific name, Dermatemys mawii) is the center piece to my research but the issues discussed impact humans and other wildlife as well. Photo by Heather Barrett

Within the LBRV, the river flows directly through the Community Baboon Sanctuary, with tributaries linking to two other protected areas: Crooked Tree Wildlife Sanctuary and Spanish Creek Wildlife Sanctuary. Together, these three sanctuaries form a critical ecological corridor that supports freshwater biodiversity, provides habitat for a wide range of aquatic and terrestrial wildlife, and serves as a hotspot for endangered species like the Hicatee turtle (Dermatemys mawii).

The Research:

My research intends to be an ongoing study focusing on LBRV communities that are increasingly affected by anthropogenic pressures, including deforestation, habitat fragmentation, industrial runoff, and unsustainable land-use practices. Among the species most vulnerable is the Hicatee turtle, a freshwater species deeply revered in Belizean Creole culture, yet increasingly at risk due to overharvesting and habitat degradation. These threats vary in scale and intensity over time, collectively undermining both the ecological health of the Belize River system and the livelihoods and food security of the people who rely on it.

My aim for this summer’s research was to explore how local fishers and conservation stakeholders perceive, prioritize, and respond to threats facing freshwater biodiversity and community well-being.

With the support of BFREE and the assistance of Wildlife Education Fellow, Samih Young, I visited several communities throughout the LBRV. I chose villages that were known to have Hicatee and that were communities whom I have met and BFREE has worked with before. Building trust through consistently showing up and having genuine concern for the community as well as the wildlife is essential to my work.

Conducting interviews with community members to hear directly from them about human-caused threats. Photos by Samih Young

The goal of the research was simple: to listen. Through interviews, informal conversations, shared meals, and storytelling, community members expressed their concerns, insights, and hopes for the future of their freshwater systems.

The results of these preliminary interviews were critical to understanding the community’s knowledge about the issues and their interest in contributing to the conservation of their natural resources. These results will help inform me about my methods and research over the next several years.

Because these are early results, I won’t describe them here. However, I will note that what became clear is that effective conservation must be collaborative; it must bridge scientific research with the lived experiences, observations, and cultural knowledge of those who have depended on and cared for these ecosystems for generations.

By investing in inclusive, community-driven conservation, this work has the potential to go beyond protecting species of ecological and cultural importance. If approached thoughtfully and inclusively, it could also strengthen community resilience, build local leadership, and affirm the essential role of community voices in shaping conservation efforts.

Sustaining our freshwater ecosystems involves more than generating fancy charts and models, it also requires building trust and forming relationships. For me, it’s about recognizing the deep connections between people, wildlife, and rivers, and understanding that the most lasting and environmentally grounded solutions are those we create together.

Special thanks to the University of Florida's Tropical Conservation and Development Program for funding this research. I also extend my deepest gratitude to the residents of the Belize River Valley for opening their doors, sharing their time and knowledge, and continuing to serve as guardians of Belize’s natural heritage.

Stay tuned as this work toward adaptive, community-centered freshwater management continues to evolve and, hopefully, inform future grassroots conservation efforts across Belize.