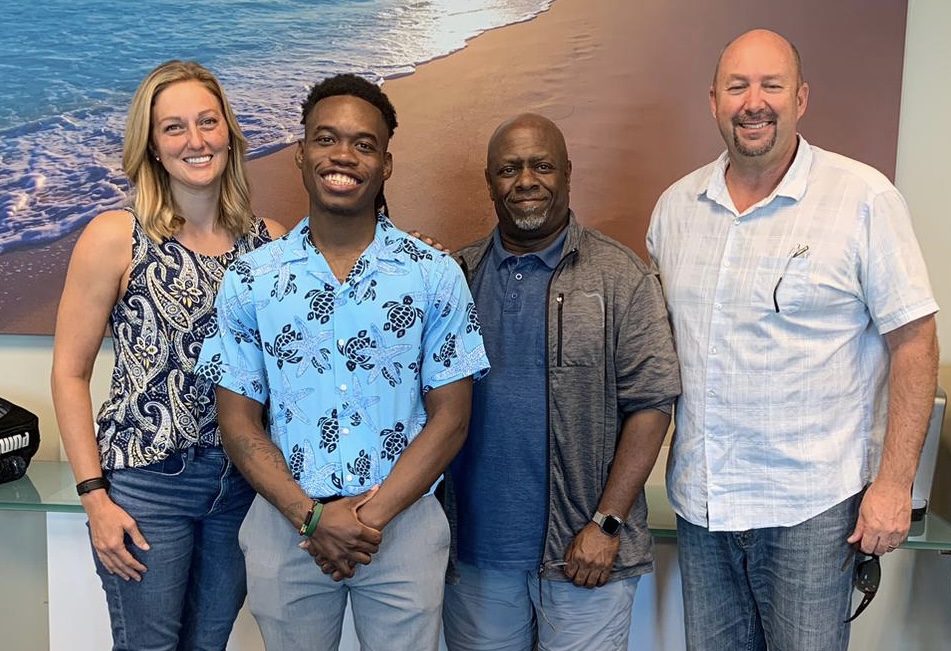

Welcome Dr. Rob Klinger, BFREE Conservation and Science Director

When Heather asked me to write something describing how I got back to BFREE, I had an internal reaction that was akin to someone asking me to have a root canal. Whether it’s rational or not, I really dislike autobiographical stuff. Making myself do something even as mundane as updating a CV is a major struggle, let alone writing a few paragraphs about “me”. I could just dutifully recite my twisting and not so traditional scholastic and professional trail: BS in Wildlife Biology from Humboldt State University (underplaying the fact it took me six years or so to complete because that time was interspersed with stints as a biological technician and fire crew member with the US Forest Service, as a deckhand on a tuna boat, as a bricklayer, and a year off to be a wandering hippy vagabond, happily traveling all over the states, Canada, and Mexico); field grunt on the statewide mountain lion survey that California attempted many years ago; ski bum and bartender (simultaneously); MS in biology from San Jose State University, where I worked on the interplay between fire, deer, and mountain lions (dream come true); a few years as an endangered species biologist and statistician for an environmental consulting firm (great practical education in bio-politics); a couple of years as the field coordinator for a project looking at the effects of off-highway vehicles on plant and animal communities in the Mojave Desert; nine years as The Nature Conservancy’s ecologist on Santa Cruz Island off the California coast; a Ph.D. in Ecology & Evolution from UC Davis, where I wandered into this incredible place called the Bladen Nature Reserve and got involved with this crazy little conservation NGO called the Belize Foundation for Research & Environmental Education; and (finally), for the last 17 years an ecologist and statistician (yeah, I’m a numbers guy) with the US Geological Survey. In and amongst all that were things like being a fire ecologist for a few years with the US Forest Service, being a member of a couple of bio-inventories in New Guinea, working with the Charles Darwin Station on the Galapagos Islands for six months, and being on the board of BFREE for well over a decade, including a stretch as the president. But absolutely none of that dutiful recitation really gets at HOW I got back to BFREE. The “how” comes down to two things: bear tracks in the snow and baseball.

Bear Tracks and Baseball

The bear tracks in the snow happened when I was young. My parents and my uncle and aunt had cabins in the San Bernardino mountains, about 100 miles east of Los Angeles. One spring we were hiking a snowy trail when my uncle (who was a consummate outdoorsman), pulled up short, pointed something on the ground out to my dad, shot my mom and aunt a glance, and started taking us in another direction. I asked my dad why my uncle had altered our course, and he said, “There were fresh bear tracks going down our trail”. Now, if you are expecting me to say I wanted to go back and find the bear you are going to be disappointed; I was scared out of my wits and wanted to go home. But, after the fact, it sparked excitement and curiosity in me about the natural world. In no time I was learning to identify mammals, birds, reptiles, plants, and animal tracks, as well as fish, hunt, and camp on my own. So, by the time I was a teenager I knew what I wanted to be: a baseball player or a biologist. Yes…baseball. I was, and remain, a big baseball fan and was a decent, though not spectacular, player as a kid. I was good enough to get invited to play in what at the time were known as “Rookie Leagues”. These were winter leagues the major league clubs set up as a low investment way to find kids who might be the proverbial diamonds in the rough. One day, after a particularly good game late in the season, I was told a scout wanted to talk to me (if I remember correctly, he was with the St. Louis Cardinals). He was a very tall, lanky older guy with white hair and a smoldering cigarette hanging out of his mouth. He came up and shook my hand and said “Klinger, sit down. I have had my eye on you and think it’s time to talk. Son, you are one of the best fielders I have ever seen. You could probably walk out on the field with any major league club and be one of the best defenders in the game. But you will never hit above .270 or .280 in AA ball.” Of course I was disappointed, but I knew he was right and that I had just received some very sage advice. I finished the season, then “hung ’em up” (meaning my cleats, as the saying goes).

Back to BFREE

From that point on, despite the winding path I dutifully recited above, I never lost sight of what I wanted or where my passion was. But how I actually got on that path was because of those bear tracks and grizzled old baseball scout. I have pursued my passion for biology with no regrets whatsoever and consider myself one of the most fortunate people on the face of the planet. And now, the thing that excites me most about being back at BFREE is getting to finally go all in working with Jake and Heather, as well as old friends like Sipriano Canti and Thomas Pop. We’ve known for years how well we work together and how much we enjoyed it, but it was always in fits and starts depending on how long I could stick around before I had to go back to my day job. Well, this is my day job now, and I could not be more happy or excited. My girlfriend Elaine is holding down our house in Bishop, California when I am at BFREE (or, more truthfully, she is at the beck and call of our eccentric cat). Elaine said, “You can tell BFREE they can have you, as long as I get a regular supply of chocolate in exchange.” That sounds like a fair trade to me, so I hope BFREE, and all of you, are prepared to have me for a good long time!